Drug-induced Cognitive Impairment Defining the Problem and Finding Solutions

Effective Date: June 18, 2014

Revised Date: June 22, 2016

Recommendations and Topics

- Scope

- Key Recommendations

- Definition

- Epidemiology

- Diagnosis

- Management

- Pharmacological Management

- Resources

- Appendices

Scope

This guideline provides recommendations for the recognition, diagnosis and management of cognitive impairment in adults ≥ 19 years within the primary care setting. The guideline focuses on Alzheimer's disease, the most common form of dementia seen in primary care. The guideline encourages early recognition and assessment of dementia and supports the development of a care plan that includes the identification of community resources for patients and caregivers.

TOP

TOP

Key Recommendations

- Do not screen asymptomatic population for cognitive impairment.

- Dementia can be masked in a typically structured office visit; third party observations can be important.

- Imaging is of limited value.

- Always involve the caregiver and plan on several visits to establish and inform patient/caregiver of diagnosis.

- Introduce advance care planning early.

- Polypharmacy and multimorbidity can both be causes and effects of cognitive impairment.

- Drug treatment has limited value; first consider non-pharmacological management of the behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia.

- Make early and regular use of adjunct services.

TOP

TOP

Definition

Definition

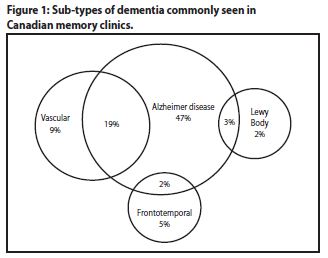

Cognitive impairment refers to mild cognitive impairment and dementia. Mild cognitive impairment refers to a cognitive decline that does not significantly impair cognitive function.1 Dementia refers to Alzheimer's disease (AD) and other dementia sub-types including vascular dementia (VaD), mixed forms of dementia and less common forms of dementia such as dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), frontotemporal dementia and Parkinson's disease dementia (PDD).

TOP

TOP

Epidemiology

Alzheimer's disease and other neurodegenerative dementia sub-types are progressive, irreversible brain diseases that lead to a decline in memory and other cognitive functions sufficient to impact activities of daily living. While Alzheimer's disease is the most common dementia, mixed dementias are becoming increasingly recognized (see Figure 1: Sub-types of dementia commonly seen in Canadian memory clinics).2

It is estimated that between 60,000 and 70,000 British Columbians have dementia, 60% of whom are female.3 Dementia prevalence is positively correlated with age.

TOP

TOP

Diagnosis

Cognitive Screening

There is no demonstrable benefit to screening asymptomatic patients. Screening is recommended with patients with cerebrovascular disease.

Signs and Symptoms

Suspect cognitive impairment when there is a functional decline in work and usual activities. This might be reported by the patient, family, friends, health care workers or other caregivers.€ Cognitive impairment symptoms tend to be gradual and insidious. Patients may hide symptoms, making it hard to detect cognitive impairment in visits that are time limited or otherwise structured.

€ Caregiver refers to the individual(s) primarily responsible for the care of the patient with dementia. The caregiver may be a family member, friend or health care worker.

The following are examples of cognitive impairment symptoms that may present during office visits and may require further assessment:

- Missed office appointments;

- Calls office frequently or inappropriately;

- Confused, forgetful or less compliant about medications;

- Defers to family member in answering questions;

- Has suffered a stroke;

- Unexplained falls and fractures;

- Frequent emergency room visits;

- Experiences late life depression, or delirium;

- Patient is unable to recall treatment instructions or recommendations from prior visits; or

- Presents signs of self-neglect (e.g., hygiene, grooming, unexplained weight loss).

Diagnostic Criteria of Dementia, Alzheimer's Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment

The diagnosis of dementia requires that the patient display the following features:4

- Impairment in at least 2 of the following cognitive domains: memory, language, visuospatial, executive function and behavior;

- Impairment causes a significant functional decline in usual activities or work; and

- Impairment not explained by delirium or other major psychiatric disorder.

To diagnose Alzheimer's disease, the patient must display the following features:4

- Cognitive changes that are of gradual onset over months to years;

- Two of the following cognitive domains are impaired: memory, language, visuospatial or executive function (memory is the most common);

- Impairment causes a significant functional decline in usual activities or work; and

- Symptoms are not explained by other neurologic disorder (including cerebrovascular disease), psychiatric disorder, systemic disorder or medication.

Although Alzheimer's disease is the most common form of dementia, patients may exhibit symptoms that fit more appropriately into other dementia sub-types (SeeAppendix A: Dementia Sub-Types [PDF, 126KB]).

A diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment is made when the patientdoes not meet the criteria for dementia either because they lack a second deficit in the cognitive domains or because their deficits are not significantly affecting their usual activities or work.

Steps to arriving at a diagnosis

- Conduct a complete medical history including a comprehensive review of medications (including over-the-counter and alternative medications).

- Encourage patient to allow collateral information be obtained from family and caregivers to assist with diagnosis. Consider administering the Alzheimer's Questionnaire (AQ) to a family member or other reliable informant (see Associated Document: The Alzheimer's Questionnaire [PDF, 119KB]).

- The following tools are recommended to provide objective evidence to support the diagnosis (the patient's cultural and educational background need to be considered when administering and interpreting results of assessment tools):

- Standardized Mini-Mental State Examination (SMMSE) to test cognition (seeAssociated Document: Standardized Mini-Mental State Examination [PDF, 690KB]);

- Clock Drawing Test to test executive functioning (seeAssociated Document: Clock Drawing Test [PDF, 147KB]); and

- Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MOCA) to test for mild cognitive impairment and early dementia (see www.mocatest.org).5

- Rule out/treat remediable contributory causes of cognitive impairment such as:

- Delirium and depression (seeAppendix B: Clinical Features of Dementia, Delirium and Depression [PDF, 131KB]);

- Hyponatremia, thyroid disorders, hypercalcemia, and cobalamin deficiency;

- Alcohol dependence;

- Adverse drug effects & polypharmacy; and

- Co-morbid diseases.6-8

- When contributory causes have been ruled out and/or treated and cognitive impairment persists, suspect mild cognitive impairment or dementia. It may take a few visits to complete the diagnostic evaluation.

- Neuroimaging is not routinely indicated.6, 9 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head is preferable to computerized tomography (CT) if available10 and should be considered when:

- The patient is less than 60 years old;

- The onset has been abrupt or the course of progression rapid;

- There is a history of significant recent head injury;

- The presentation is atypical or the diagnosis is uncertain;

- There is a history of cancer;

- There are new localizing neurological signs or symptoms;

- There is a suspicion of cerebrovascular disease;

- The patient is on anticoagulants or has a bleeding disorder; or

- The patient has a combination of early cognitive impairment with urinary incontinence and gait disorder (to exclude normal pressure hydrocephalus).

- Consider using the Global Deterioration Scale to stage dementia (SeeAssociated Document: Global Deterioration Scale [PDF, 117KB]).

- When available, consider referral‡ to secondary services (e.g., specialist, social services, occupational therapist) for the following:

- Diagnostic uncertainty or atypical features;

- Rapid decline in cognition;

- Under 65 years of age;

- Management issues that are difficult to resolve; or

- Risk of harm to self or others.

‡ Where referral is not possible, a telephone consult may be appropriate. Reimbursement for consultations may be available through the Facility and Community Conferencing Fees billing items; information found through GPSC: www.gpscbc.ca.

Diagnosis Disclosure

Dementia diagnosis should be disclosed as soon as possible, preferably with a caregiver present. Significant stress can occur to patients and their caregivers; therefore, the timing and extent of disclosure should be individualized and carried out over several visits. Make an early referral to other support resources (seeAssociated Document: Resource Guide for Physicians [PDF, 268KB]). Provide the patient with theAssociated Document: Guide for Patients & Caregivers (PDF, 274KB).

Exceptions to disclosing dementia diagnosis to the patient include probable catastrophic reaction, severe depression or severe dementia.

Carefully consider mild cognitive impairment diagnosis disclosure to avoid prompting needless anxiety. Reassure the patient and caregiver that it is premature to diagnose Alzheimer's disease or prescribe drugs. Discussing the possibility of progression to dementia may facilitate patient participation in monitoring their cognitive decline. Schedule regular follow-up visits (e.g., every 6 months) to monitor possible progression of cognitive deficit. Suggest healthy brain activities, e.g., regular exercise, word games, socialization (seeResource Guide for Physicians [PDF, 268KB]).

TOP

TOP

Management

Physicians are encouraged to deliver timely, individualized care to the patient and their caregiver and to support patient independence at a level that is appropriate for their cognitive and physical capabilities. Always start with non-pharmacological interventions.

Specific suggestions include:

- Establish a register of patients with cognitive impairment to aid in scheduling timely patient visits;

- Reassess a patient at planned visits dedicated solely to the care of cognitive impairment (e.g., regular drug reviews, measure cognitive decline and functional changes, reevaluate multimorbidity and polypharmacy¥ for their effects on cognition);Ω

- Involve the patient and caregiver in setting goals and making decisions. Consider use of clinical action plan (flow sheet). SeeAssociated Document: Clinical Action Plan (flow sheet) (PDF, 130KB); and

- Most dementia patients are geriatric patients with other issues. Consider vaccinations, vitamin D supplementation, falls risk assessment and exercise prescriptions. Refer to Clinical Practice Guidelines for other chronic disease guidelines which may be useful.

¥ Polypharmacy is a standalone risk for morbidity in all elderly patients; the cognitively impaired are especially at risk.

Ω Physicians may be eligible for complex care incentives for the management of complex patients; see GPSC for more details: www.gpscbc.ca.

General Care and Support for Community Dwelling Patients

Consider the following general care and supplementary supports for patients:β

- Memory

- Aids like calendars, diaries and telephone reminders;

- Keeping keys, glasses, wallet in same designated place ("landing spot"); and

- Accompaniment to appointments.

- Behavioural Symptoms

- If patient is considered at risk to others or themselves through reactive, repetitive and wandering behaviours; see the Best Practice Guideline for Accommodating and Managing Behavioural and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia in Residential Care (PDF, 782KB) and its related algorithm (PDF, 2.71MB) for guidance on managing these; and

- Carrying identification when out alone; use of an ID bracelet.

- Nutrition

- Weigh regularly to monitor for weight loss;

- Have the caregiver monitor the refrigerator for food safety; and

- Meal support services (e.g., delivered prepared meals or pre-prepared frozen foods).

- Shopping

- Use of lists when shopping;

- Shopping assistance from caregiver; and

- Meal support services (e.g., delivered prepared meals or pre-prepared frozen foods).

- Household Safety

- Monitor kitchen for mishaps (e.g., fires, burned pots); have stove unplugged or automatic stove turn-off device installed;

- Functioning smoke detectors;

- Assess home for other safety hazards (e.g., unsafe smoking, firearms in the home);

- 911 stickers for telephones;

- A personal alarm service in case of patient accident; and

- Referral for home assessment through Home & Community Care.

- Medication Management

- Use blister packages/dossette trays and suggest caregiver supervision to improve safety and compliance; and

- Medication monitoring through Home & Community Care.

- Hygiene

- A bathing assistant or bath program through Home & Community Care.

- Socialization

- Awareness that patients with dementia may become socially withdrawn; and

- Referral to an adult day center through Home & Community Care.

- Financial & Legal Issues

- Discuss advance care planning as early as possible (e.g., refer to Advance Care Planning Guide [PDF, 4.0MB] for aid in discussing sensitive topics like tube feeding. See also No Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation form; and

- Encourage patient to have an up-to-date will, a power of attorney agreement for financial management, a representation agreement for health management and/or an advance directive.

- Driving

- Assess patient's competence for driving (see Driver Medical Fitness Information for Medical Professionals);

- If there are concerns about a patient's functional ability to drive, consider referral to Drivable to have their skills assessed;

- Under Section 230 of theMotor Vehicle Act, a physicianmust report to RoadSafetyBC (formerly the Office of the Superintendent of Motor Vehicles) if:

- A patient has a medical condition that makes it dangerous to the patient or to the public for the patient to drive a motor vehicle; and

- A patient continues to drive after being warned of the danger.1

- To supplement or replace driving encourage patient to register with HandyDart and TaxiSavers (seeGuide for Patients & Caregivers [PDF, 274KB]).

- Self-Neglect, Neglect and Abuse

- Be aware of the risks for patient abuse/neglect;

- Help assess patient abuse/neglect using the Re: Act Adult Abuse and Neglect Response Flow Sheet and Assessment Guide (PDF, 471KB);

- Report cases of abuse to designated agencies; and

- In extreme cases of self-neglect use the Mental Health Act (form 4).

- Mental Health and Specialty Services

- Be aware that dementia may co-exist with other complex mental health conditions;

- Involve mental health teams and resources, such as Community Mental Health Services, to help in distinguishing depression from dementia, and assessing and treating significant behavioural problems and managing caregiver stress; and

- Involve allied health professionals (e.g., Home & Community Care case managers, mental health teams, pharmacists, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, dietitians).

- Caregiver Support

- Discuss needs, coping strategies, support system and stress management with caregiver (respite care through Home & Community Care); and

- Aid in coordination, communication and planning during transitions between care environments.

β All suggested resources are referenced in either the Resource Guide for Physicians and/or the Guide for Patients and Caregivers.

Cognitive Impairment in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Groups11, 12

The assessment and management of cognitive impairment in diverse individuals can be challenging for several reasons:

- Communication difficulties, cultural factors, low education and literacy impact formal cognitive screening, with poor inter-rater reliability – use interpreter services to assist in more accurate patient screening and assessment;

- Dementia symptoms may be unfamiliar or viewed as part of the aging process, and there may be stigma to mental health issues, resulting in diagnosis delay – provide culturally sensitive patient information on dementia to patients and families;

- Language barriers may result in a lack of awareness of community supports – provideGuide for Patients & Caregivers (PDF, 274KB);

- Community supports may not provide culturally appropriate care, resulting in lack of adoption of these services and increase in caregiver stress; and

- Families may share caregiver responsibilities by rotating the residence of the patient amongst family members – this is generally discouraged as it confuses the patient with dementia and complicates the provision of services between the staff of many agencies and the extended family. One familiar, safe and secure environment is encouraged.

TOP

TOP

Pharmacological Management

The use of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs)/memantine is controversial. While data from clinical trials report statistical evidence of benefit, clinical benefits are unclear. It should be noted that drugs may benefit only a small minority of patients, and the evidence for long term use is insufficient. Short term benefits (6-12 months)may include cognitive, functional, and global improvement.13 However, patients and their caregivers should be advised that benefits are limited, and that side effects and drug interactions are common. End points for discontinuation of medication should be discussed.

If considering pharmacological management of Alzheimer's disease, seeAppendix E: Comprehensive Pharmacotherapy Information for Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors and Memantine (PDF, 155KB).

Pharmacotherapy of Behavioural and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD)

It is preferable to first attempt to treat BPSD using behaviour or environment modification rather than drugs. Identify and correct reversible causes of the behavior first. For detailed guidance on managing BPSD see Best Practice Guideline for Accommodating and Managing Behavioural and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia in Residential Care (PDF, 782KB) and its related algorithm. In very specific situations, antipsychotics have been used to treat symptoms of agitation, aggression, or psychotic manifestations. Typical ("first-generation") antipsychotics, such as loxapine, and atypical ("second-generation") antipsychotics, such as olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone, may be used.

TOP

TOP

Resources

References

- Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General: RoadSafetyBC. 2016 CCMTA Medical Standards for Drivers With BC Specific Guidelines [Internet]. Victoria: BC Provincial Government; 2016 April [cited 2016 Aug 2]. Available from: http://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/driving-and-transportation/driving/publications/2016-ccmta-guide.pdf.

- Feldman H. Levy AR, Hsiung GY, et al. A Canadian cohort study of cognitive impairment and related dementias (ACCORD): Study methods and baseline results. Neuroepidemiology. 2003;22(5):265-74.

- Ministry of Health. The provincial dementia action plan for British Columbia: priorities and actions for health system and service redesign. [Internet]. Victoria: BC Provincial Government; 2012 Apr [cited 2013 Aug 2]. Available from: www.health.gov.bc.ca/library/publications/year/2012/dementia-action-plan.pdf (PDF, 7.0MB).

- McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263-9.

- Nasredddine Z, Phillips N, Bedirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2005;53:695-699.

- 146 Approved Recommendations Final. Third Canadian Consensus Conference on Diagnosis and Treatment of Dementia, Montreal, March 9-11, 2006. [Internet]. 2007 Jul [cited 2013 Aug 2]. Available from: www.cccdtd.ca/pdfs/Final_Recommendations_CCCDTD_2007.pdf (PDF, 96KB).

- Galvin JE, Sadowsky CH. Practical guidelines for the recognition and diagnosis of dementia. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25:367-82.

- Hort J, O'Brien JTO, Gainotti G, et al. EFNS guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Alzheimer's disease. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17:1236-48.

- Patterson CJS, Gauthier S, Bergman H, et al. The recognition, assessment and management of dementing disorders: Conclusions from the Canadian Consensus Conference on dementia. CMAJ. 1999;160(Suppl12):S1-15.

- Gauthier S, Patterson C, Chertkow H, et al. 4th Canadian Consensus Conference on the diagnosis and treatment of dementia. Can J Neurol Sci. 2012;39(Suppl5):S1-8.

- Alagiakrishnan K. Ethnic elderly with dementia: Overcoming the cultural barriers to their care. Can Fam Physician. 2008 Apr;54:521-2.

- Shah A. Cross-cultural issues and cognitive impairment. [Internet]. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists; (unknown) [cited 2013 Aug 2]. Available from: www.rcpsych.ac.uk/pdf/dementia%20%20culture.pdf (PDF, 18KB).

- Birks J. Cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006, Issue 1. Art. No.:CD005593.

TOP

TOP

Diagnostic Code: 290

Appendices

- Appendix A: Dementia Sub-Types (PDF, 126KB)

- Appendix B: Clinical Features of Dementia, Delirium and Depression (PDF, 131KB)

- Appendix C: Delirium Screening and Assessment Tools – CAM & PRISME (PDF, 136KB)

- Appendix D: Depression Screening Tools (PDF, 133KB)

- Appendix E: Comprehensive Pharmacotherapy Information for Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors and Memantine (PDF, 155KB)

- Appendix F: Medication Table (for the treatment of cognitive impairment in the elderly) (PDF, 144KB)

Associated Documents

The following documents accompany this guideline:

- The Alzheimer's Questionnaire (PDF, 119KB)

- Standardized Mini-Mental State Examination (PDF, 690KB)

- Clock Drawing Test (PDF, 147KB)

- Montreal Cognitive Assessment (external website)

- Geriatric Depression Scale (short form) (PDF, 136KB)

- Global Deterioration Scale (PDF, 117KB)

- Clinical Action Plan (flow sheet) (PDF, 130KB)

- Guide for Patients & Caregivers (PDF, 370KB)

- Resource Guide for Physicians (PDF, 268KB)

TOP

TOP

This guideline is based on scientific evidence current as of the effective date.

This guideline was developed by the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee, approved by the British Columbia Medical Association and adopted by the Medical Services Commission.

The principles of the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee are to:

| Contact Information Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee PO Box 9642 STN PROV GOVT Victoria BC V8W 9P1 E-mail: hlth.guidelines@gov.bc.ca Web site: Clinical Practice Guidelines |

DisclaimerThe Clinical Practice Guidelines (the "Guidelines") have been developed by the Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee on behalf of the Medical Services Commission. The Guidelines are intended to give an understanding of a clinical problem and outline one or more preferred approaches to the investigation and management of the problem. The Guidelines are not intended as a substitute for the advice or professional judgment of a health care professional, nor are they intended to be the only approach to the management of clinical problems.We cannot respond to patients or patient advocates requesting advice on issues related to medical conditions. If you need medical advice, please contact a health care professional.

TOP

TOP

Drug-induced Cognitive Impairment Defining the Problem and Finding Solutions

Source: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/practitioner-professional-resources/bc-guidelines/cognitive-impairment